The first international financial crisis in the 21st century: causes and effects

Carlos Parodi Trece

The first decade of the 21st century saw an international financial crisis comparable only to that of the 1930s, known as the Great Depression. The crisis occurred in the United States financial system, and from there it expanded to the rest of the world, particularly to Europe, which made it a phenomenon of the advanced economies, an aspect that differentiates it from the other crises that occurred in previous decades.

The crisis erupted in September 2008 and consisted of the virtual collapse of the United States financial system, considered one of the most advanced and complex in the world; in essence, similar to other financial crises, it was a crisis of over-indebtedness, which left us with a lesson: no-one can indefinitely spend more than they earn.

The high degree of global integration of the national financial systems led to a rapid spread of the crisis, the maximum manifestation of which occurred in September 2008 with the fall and subsequent disappearance of investment banks, emblems of Wall Street, something that triggered a synchronized recession globally in 2009. Governments around the world then launched economic stimulus programmes, involving increases in public spending, often financed by external debt, so that the reduction in private investment caused by the crisis was temporarily replaced by public investment.

However, the larger debt generated a fiscal crisis, which largely explains the subsequent European situation. A crisis of the magnitude described is a multi-causal phenomenon.

FINANCIAL DEREGULATION AND THE ADVANCEMENT OF ICT WERE KEY

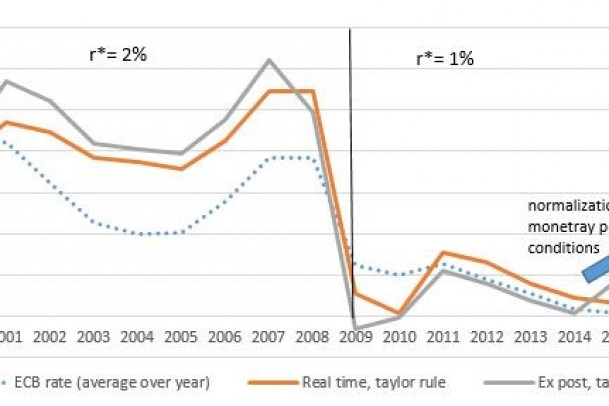

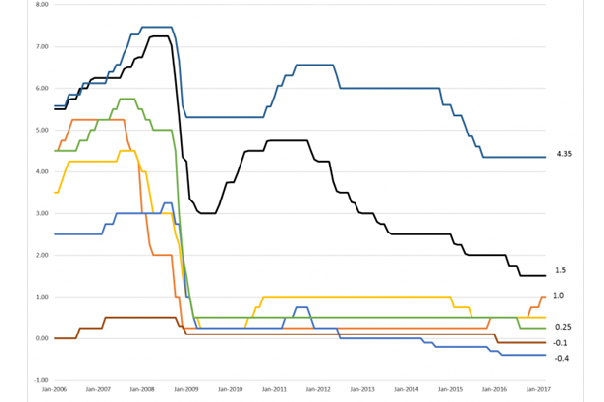

In fact, financial deregulation and the advance of computer technologies and the Internet were key factors that combined with others, such as the reduction of the Federal Reserve's interest rates, formed an explosive combination. The result was sophisticated financial products whose complexities prevented the financial system from fulfilling one of its main functions: measuring risk.

The result was exotic, complex and opaque financial products, which made measuring risk difficult.

Up to 1999, there were two types of banks in the United States: commercial banks which received savings and gave out loans covered by deposit insurance, and investment banks which receive money from users and place it on the stock market or other alternatives; these have no deposit insurance and since 1999 were merged.

Commercial banks provided mortgage loans to subprime clients, creating a housing bubble; people bought houses because they could easily access bank loans; this happened because the banks in turn sold the loan on to investment banks, who placed them on the stock market and resold them to any investor in the world.

The system worked so long as houses rose in price, which was in turn fuelled by the credit boom. The bursting of the housing bubble at the end of 2005 caused banks to repossess homes as housing prices nosedived, since it no longer made sense to continue paying the loan when the value of the home was lower than the outstanding debt with the bank.

ECONOMIC HAVE BEEN REPEATING THEMSELVES FOR FOUR CENTURIES

The absence of adequate regulation and supervision in a context of technological advances was at the heart of the crisis.

Emerging economies were infected by the crisis in the advanced countries through commercial and financial channels. The first one manifested itself in the reduction of the demand for exports, while the second was in the increase of credit. Both contributed the expansion of the recession in 2009. However, unlike European economies, countries such as Peru financed the economic stimulus programme with savings from previous years, so there was no need to increase indebtedness. This is to say, it maintained macroeconomic soundness in a global environment characterized by the opposite.

Despite differences in details, the crisis described here is nothing new. Since the seventeenth century with the "tulips" crisis in Holland, it has been a recurring phenomenon. The initial credit boom creates a bubble in the price of whatever asset, which in most cases have been stocks or housing.

When prices stop rising, the bubble bursts and the boom is reversed: the result is a financial crisis whose scope and magnitude depends on the participation of financial systems. Economic history matters, as speculative bubbles have repeated themselves with different assets for four centuries.