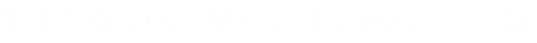

In the mid-nineteen thirties, there were more dictatorships in Europe than democracies. All of them, and according to the situation of the time, were enormously nationalistic and had little sympathy with the freedoms that we enjoy today in these same countries. With the exception of the Czechoslovaks, the rest of Europeans from the centre and the east lived in autocracies, standing as the maximum exponent of this majority the National Socialist Germany and the Italy of Mussolini. Eighty years later, old ghosts of the continent have been revived due to the results of the European Parliament elections. Something that was believed to be well-buried in the European political culture as were the thoughts and parties of the Far Right, have been revived in recent years with the corresponding concern of democratic societies that, in these times, dominate the life of Europe.

AN IGNORED PHENOMENON

On October 11th, 2008, Jörg Haider, Governor of Carinthia, a region in southern Austria, died in a traffic accident. This fact particularly struck a chord in the European media, given that the politician born in Klagenfurt was part of the Union for the Future (BZÖ) party, a far-right xenophobic party whose sympathies for certain elements and policies of the Hitler's regime made its position on certain issues clear. Moreover, only two weeks before, the BZÖ and a party of them tendency, the FPÖ, had gained 30% of the votes in the Austrian parliamentary elections. This mixture of Austria and the Far Right surprised and alarmed equally. Despite the fact that the global economic crisis had erupted the month previous to this, openly extremist parties had already gained almost a third of parliamentary power in a country such as Austria that thought it was advanced on democratic issues.

From this point, the phenomenon of the Far Right began to expand in Europe at the same pace, and this became more visible to public opinion in many countries. It was reproducing a phenomenon that had not had this level projection on the continent for many decades. Extremist parties already existed in many European countries, but they had always had a quite low level of support in the elections and a marginal political presence, however now they began to grow as the crisis intensified. Formations like the National Front in France, the UKIP in the United Kingdom, Golden Dawn in a battered Greece or the Hungarian Jobbik were beginning to be common names in the general public's ears. The traditional parties, whether popular, Christian Democratic, socialist or liberal, had lost more and more ground as a consequence of their mismanagement of the crisis and the popular disenchantment that it provoked of the political system and its parties, leaving a gap which, with enormous skill was being occupied by these formations with a simple and direct discourse, although potentially dangerous for European democracies. Six years after Haider disappeared, the bubble continues to swell without knowing when or how it will stop.

A MESSAGE THAT DOES NOT GROW OLD

The decline of the real economy and the absence of solutions to address the bleeding towards impoverishment has been due mainly to the political inability to design effective solutions, along with the fact that many of these solutions had to go through the consent of most of the twenty-seven member countries of the Union. The lack of a way to do this cooperatively, and the desire to take refuge under its wing and wait for the storm to pass has been seen by a large sector of each society as a sign of incapacity, and at the same time as a confirmation of the inefficiency of certain mechanisms of community actions.

All these mortal drifts constitute the perfect breeding ground for the empowerment of Far Right formations, in addition to situations of disaffection, concern and even despair as regards where they live. Messianic solutions that appeal to feeling, to the unity of a group -often the nation- against a common and external enemy.

Since nationalism broke out in Europe at the beginning of the 19th century, this type of harangue has been a constant that has given the continent more pains than joys.

As a general rule, the tools that these political parties use to travel the road to power are not numerous, but they are effective. The first is to find a threat to the majority group to which the discourse of these parties is addressed, which with a few exceptions becomes virtually all of the census. Traditionally, they have been minority groups with which a distinction between "we" and "they" can be quickly established, both visually and identitatively. As a rule, in this process of differentiation, immigrants are the first to become a target for far-right parties. With the passage of time, in many European countries significant immigrant population sectors have been formed, which are better or worse integrated into their new country, and participate in its economic, social and political life.

Easy arguments -simplistic rather- such as the hoax "come to take away our work" or the "use up all our social benefits" penetrate quickly into the country's working and middle classes.

In this way, this group, that of the immigrants, is demonized by the almost everyone under pretexts that are not quite made explicit but are quite easy to assimilate. If we add to this in a subtle and moderate way -few parties dare to do it in blatantly- racist or ethnocentric distinctions, the cocktail becomes a time bomb.

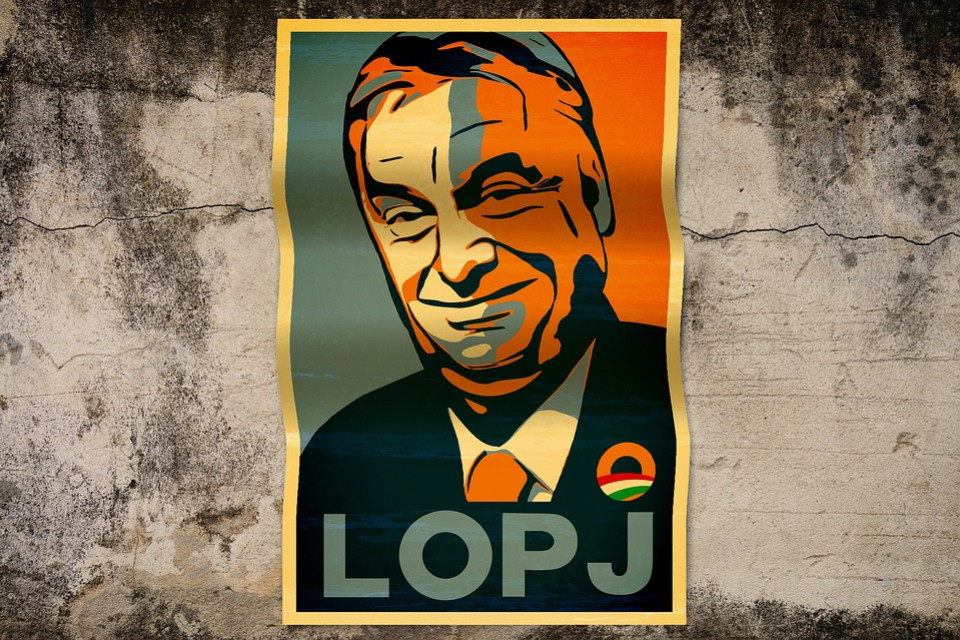

Neither is it that immigrants are the only resource of these type of parties and ideologies. It is easy to make them the scapegoats since there are foreign communities large enough to try to convert them into national danger in almost all European countries. Despite this, the spectrum of "potential enemies of the nation" can also be extended to other groups. In Hungary, as there are not too many immigrants easily distinguishable from Hungarians -such as Africans or Asians- the Jobbik, the third political force in the country, has concentrated its efforts on persecuting gypsies and Jews -in Hungary there are 700,000 gypsies-, since it considers that, in addition to not being racially comparable to the Hungarians, they foment delinquency and are a core of poverty in the country.

Being Muslim is also a risk to the survival of the country and social stability according to these groups.

Many African and Middle Eastern immigrants profess Islam, and when they arrive in a new country in Europe, they still maintain their faith. However, since 9/11 and with the rise in that decade of transnational Islamist terrorism in Europe, a negative bias towards Muslims has been internalized in certain groups and sectors. Thus, in countries where there are numerous Muslim communities -between 3% and 6% of the total population- such as France, the United Kingdom, Belgium and the Netherlands, the trick of Islamophobia has been that it is usual to place them in the role of a threat to the rest of society. In addition, the predictions that the proportion of Muslims will increase in these countries during the next decades, as well as the frequent political debates around certain customs in Islam such as women having to wear veils, have fuelled extremist groups' rhetoric.

In this route to find a scapegoat for the country's poor progress, immigrants and other religious or ethnic groups have lost prominence in recent years in favour of an unsuspected agent: the European Union. Since 2008 and as the crisis has deepened, the follies and fierce conditions imposed by the Union to help countries in difficulties have created huge disaffection towards community structures, both in the popular sense and in some sections of the ideological spectrum. Thus, particularly in the last five years, many right-wing political groups accuse the EU directly of being a fundamental cause in the deterioration of the economy and the social situation of the country. Under this premise, these extremist parties of the Right propose to dissolve the community and return to a Europe of nations without integration -Europhobes-, while other parties claim that community integration cannot not advance more than where it is already at, and if possible, they will try that some competences ceded by the member states to the Union are returned -Eurosceptics-.

THE SLOW DRIFT TOWARDS THE RIGHT

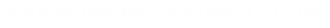

The phenomenon we discussed has not happened suddenly. Although it is true that its successes have surprised us, concretely in almost 13% of seats in the 2014 European Parliament elections. The impact is conditioned to the fact that there are simultaneous elections in twenty-eight countries in a specific moment, facilitating the analysis more than doing it country-by-country. So, those elections from May 22nd to 25th were the time for all those parties to stick their chest out. And did they ever. For many, that election night and the day after was worrisome because of this boom, but the results of these political parties had not been achieved overnight. They had been brewing for a long time.

Without going back to the beginning of time to analyze the trajectory and the rise of these groups, already in 1999 they had a small but representative presence. In that year, when the elections to the European Parliament in mid-June gave rise to the sixth EU legislature, the party for the Union for Europe of the Nations was the one that was the lightening rod for all this Eurosceptic and extremist tendency. Without much consistency, it was joined by MEPs from the French National Front or the Danish People's Party to form a platform that would bring results in the following elections.

In 2004, the newly inaugurated "Europe of the Twenty-five" had to decide on parliamentary composition.

By that time, parties of the Far Right had found a degree of shelter in enough places. Only two years before, France convulsed when they saw how Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the right-wing National Front party, managed to get through to the second round of the presidential finals after having beaten the socialist candidate by a few tenths of a point. A common front was formed to prevent the right-wing winning, and Jacques Chirac did so, the centre-right candidate, who closed the ranks of society against this type of party. In the same way, since the Euro came into force in that same year, which in the first instants caused some inflation in many countries; immigration pressure had been quite strong in the south and east of the continent and the adoption of freedom of movement in an eastward expansion -which took place a month before the elections- made misgivings about conciliatory policies of the EU increase.

The ten new countries to be integrated favoured the empowerment of the Right-wing.

They were usually countries that had been tutored under Soviet power for half a century, and once freed from this bloc, quite strong identity movements had occured, always seeking their uniqueness as a nation, be it for their history, their culture or their religion, so that in its re-entry into a block like the Union, many voters in Eastern Europe opted for an option that struggled to maintain this national identity.

With this situation, the results of these political parties were frankly superior. The party Independence and Democracy, led by Nigel Farage, got 37 MEPs with a mix of British UKIP MPs or Poles from the League of Polish Families, which were complemented by the Union for Europe of Nations, that almost doubled its representation thanks to the contributions of the Italian National Alliance and the Poles for Law and Justice. These two groups were also joined by parties that went unaligned within the group of "not ascribed", where it is usual for these formations to be, given that they find no place in major political parties at European level. Here we had from the National Front of Le Pen to the Flemish nationalists or an Italian party led by Mussolini's granddaughter. Gathering all together, this constituted 87 MEPs, only one less than the third political force in the European Parliament, the Party of Liberals and Democrats, although separately Eurosceptics had obtained three more election points than European liberals.

In the following years, more parties from all over Europe joined this ideology, which although they did not advance in votes or MEPs for 2009 -in fact, they lost almost half of the seats-, accumulated more formations in their fold, in the context where we were already in crisis, they would have five years to work bit-by-bit in their countries and thus force the situation in which we find ourselves today. In 2009 parties would appear that would be fundamental five years later, such as the True Finns, the Dutch Freedom Party or the Hungarian Jobbik, and all this without all the support that would appear after the new political parties that would appear until 2014.

And so the day arrived. Between May 22nd and 25th, the Union voted. and in almost every country, from the first, Germany, to the last, Sweden, the option that swung between Euroscepticism and extremism on the Right was strongly rewarded.

From the Neo-Nazi MEP from Germany to one out of every three European MEPs being from Marine Le Pen's National Front, the successor to their progenitor and architect of the success of the far-right formation. In the Nordic countries, more radical formations also discovered oil, as well as in Austria, Hungary and the already-known Greek neo-Nazis of Golden Dawn, which would occupy three seats in the European Parliament until 2019. And that without counting the strongly Eurosceptic options, such as the British of the UKIP or the moderation that many formations of the Polish Right do not know. Thus, differentiating within all this mixture of right-wing Euroscepticism, of those 130, we can consider about 95 right-wing, which would mean that 12.6% of the European Parliament's caucus will be occupied by this political option for the next five years with MEPs from fifteen of the twenty-eight countries.

Despite these results, the concern is not in the use they make of their power within the European Parliament -which borders on 13% of seats, nothing excessive either-, but the role they might play within their respective countries in national politics. There is no country of the Union that is governed by a political formation of this style, but it is no less true that in recent years their share of the vote is increasing. The May 2014 contest was but a stop along the way for these political parties, a measure of their electoral health in response to its true objective: to compete in national, regional and local elections in their countries. In the UK it is not uncommon to find current surveys that position the UKIP as the third political force, a fundamental position for the next one who wants to reach Downing Street, as it is not strange that the Marine LePen party in France is the favourite according to opinion polls about affinity, above a Socialist Party surpassed by the crisis and that has been forced to also make cuts to reduce expenses.

It is not easy to predict which trajectory this phenomenon will follow. That they gain or lose power will always be in the hands of those who put their vote in the ballot box. Perhaps, on reflection and looking at the history of the continent under this type of thinking should be enough to find the solution.