In 2012, then European Commissioner for Trade, Karel De Gucht, explained the EU trade policy in times of protectionism at a conference at the Centre for Practical European Political Excellence. This was their presentation:

Do we really live in an age of protectionism? I have to say that there is evidence to the contrary. In the wake of the greatest economic reversal since the 1930s, we can argue that in protectionist terms, governments have been quite moderate. For example, in its most recent report to the G20 on protectionism, the WTO and its members found that, although there have been new restrictions, they only affect about 2% of world trade.

In addition, many countries are currently liberalising trade through bilateral and regional free trade agreements. The European Union is negotiating with members on almost every continent. In East Asia alone, there are currently 43 regional or bilateral free trade agreements under negotiation.

So, where is the problem? There are several. First, even if the amount of trade affected by the new government restrictions installed since the crisis is proportionally small, European exports have been affected at twice the average rate. In addition, the trade volume may be small, but there are 425 current measures, not to mention the fact that 131 new measures were introduced in the last year.

Secondly, these recent developments are even more worrisome because the logic given by governments is no longer simply the contingency of the crisis. Instead, they are often justified as allegedly vital parts of strategic industrial policies. This type of language suggests an unwanted permanence.

THE FINANCIAL FAILURE GENERATED QUESTIONS ABOUT THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE MARKETS

And thirdly, while bilateral liberalisation is a necessary tool, the fact that despite our efforts, our trading members have not been able to sit down at the table and conclude the Doha Round of negotiations last year is indicative of this general trend.

So, although things could be worse, we would be naive if we rest on our laurels or believe that our work is well done.

Instead, we have to deal with the fact that there has been erosion of broad political consensus on the benefits of open markets, not at European Union level, but rather in some other parts of the world.

Despite the failures here and there, in the last decades we have achieved a general agreement on where we were going. Currently, I am afraid that the final point has gone out of focus for some. Given the dramatic economic events of recent years, this may not be surprising.

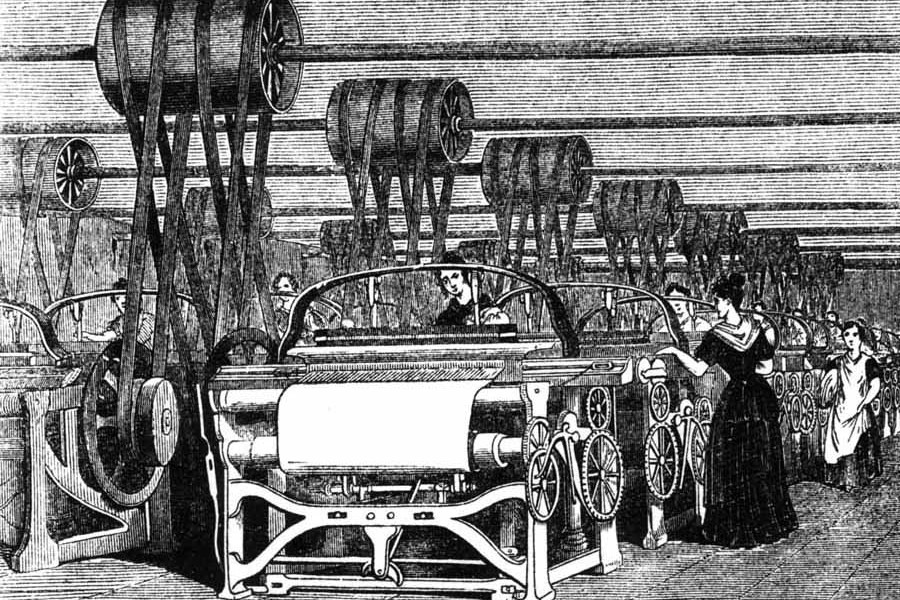

Ins prior to 2008, the debt boom caused the derailment of our financial system, which contributed to bringing the government treasury reserves to a quite low level. This failure of the financial markets raised questions about the effectiveness of all markets. Additionally, the pain of mass unemployment made those questions even more acute. If this were not enough, globalisation has radically altered the international division of labour. Many previous elements of the economic landscape have gone down in history. Moreover, for some, the mere existence of a successful economy such as China's, with its hybrid system of state capitalism, represents an invalidation of free trade consensus.

On one hand, China's economic miracle has been based on the abundance of labour and the gradual opening of markets, not on government intervention.

To be clear, I am certainly concerned about the effects of some of China's policies. However, market laws have not changed. The company that benefits from the generosity of the government today will feel the weight of their dead hand tomorrow. In the same way, countries that now choose to adhere to open markets and free competition will be rewarded with dynamic, flexible and innovative companies in the future.

On the other hand, unregulated markets are not the same as open markets. We have reinforced our controls in the financial sector, but we have to avoid the temptation to reinforce trade controls at all costs. On top of all this, the latest economic understanding of how trade really works shows us that, in the world economy, we are all even more intertwined with each other than we thought. In this new paradigm, trade is no longer simply the exchange of goods and services, but rather the exchange of added value.

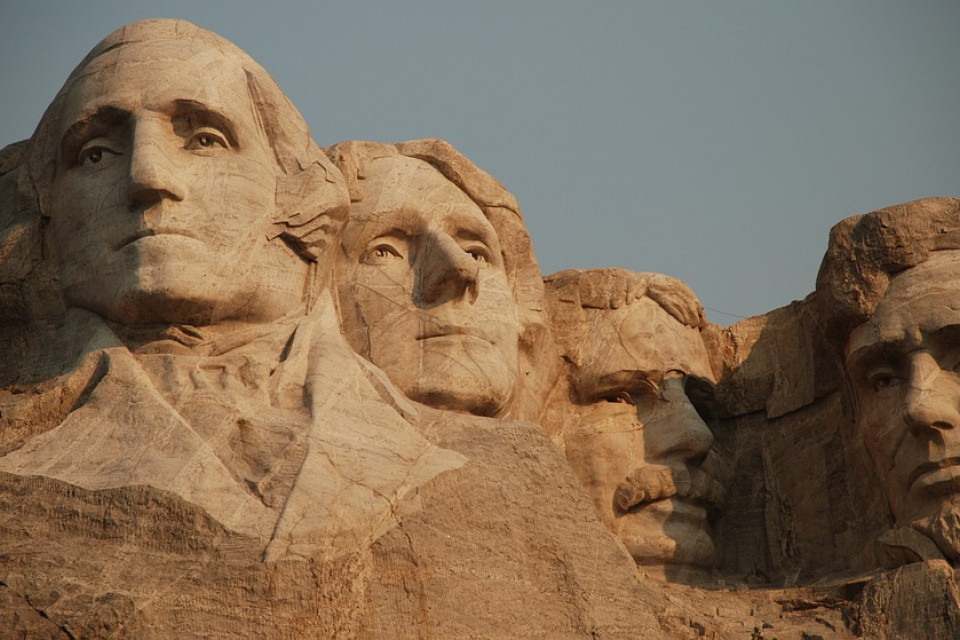

AS EUROPEANS, WE HAVE LITTLE TO FEAR FROM TRADE

Global output chains mean that the products we consider imports are often composed of components and designs from Europe. The most significant examples are smartphones.

According to our commercial statistics, both the iPhone and the Nokia N95 are manufactured in China, but 12% and 54% of their value respectively are added by European workers.

We saw this new reality when many European companies discovered that their altered and stressed output chains suddenly broke after last year's natural disasters in Japan and Thailand. Why would we choose to have the same effect in making protectionist policy decisions? Whatever, as Europeans we have rather little to fear from trade. There are 36 million people that have jobs thanks to our open borders, and trade flows cross them in both directions. We are the world's largest exporter of manufactured goods and services, with a solid and constant share of 20% of all goods exported worldwide.

Moreover, we need trade to guarantee our economic future. From 2015 on, 90% of global growth will happen outside our borders. We have to commit ourselves to the dynamism of Asia and Latin America to be able to bring back part of that growth to Europe. Boosting trade is one of the only ways to increasing growth without using public finances. However, I'm not saying we should bury our heads in the sand and pretend that nothing has changed. We know that many Europeans are suffering the consequences of the crisis. If we want to maintain their support for trade, they have to perceive that it is not only free but also fair. So, this means finding a balance between staying open and pushing for opening elsewhere. and fortunately our European trade policy in times of protectionism is exactly that.

So, what does this mean in practice?

The main tool we have is the negotiations. In consequence:

We seek to deepen our economic relations with two of our main trading members: the United States and Japan;

We hope to conclude some of our most advanced free trade agreements negotiations quite soon; for example, with India, Canada, Singapore and Malaysia;

Additionally, if the Member States and the European Parliament agree, we will put three agreements concluded provisionally into effect this year: with Colombia, Peru and Central America.

THE EUROPEAN SHOPPING MARKET IS OPEN

We can put here a good example of the results, which is the Korea Free Trade Agreement with the EU. Due to the comprehensive treaty that we were able to negotiate, approximately 70% of bilateral trade is already tax-free. In the first six months that it was in force, there was an increase of our exports equivalent to 16% per year. In addition, our trade deficit with Korea fell below 10 thousand million Euros, for the first time in more than 10 years.

But beyond negotiations, we also have other mechanisms to offer more commercial openness. An example of how we approach this is the proposal we proposed to open public procurement markets around the world. If approved, it would give us a new impetus in international procurement negotiations.

Currently, the European procurement market is openThis benefits. European consumers and taxpayers.

However, it means that we have little to negotiate with our trading members, whose markets are often closed to our exports. What's new in our proposal is that it allows us to introduce a credible threat in those negotiations. It allows us to tell our members that, if they persist in keeping their markets closed, they will lose the boost to the competitiveness of open procurement when their companies no longer have access to our lucrative public markets here in Europe. This is not a protectionist line of reasoning. As I said, I'm still a champion of open markets. However, if we want to have an effective commercial policy, we have to convince others to also open up and that can only be argued from a position of strength.

I know that powerful mechanisms such as this do carry risks, so our proposal guarantees that they are under the strict control of the Commission. Moreover, let me be clear on this: I do not want to use them if it is not necessary. However, with this proposal we are making a clear statement of intentions. We are not doing this lightly. Beyond acquisitions, we are already making full use of all commercial instruments at our disposal to guarantee respect for commercial norms.

THESE ARE NOT EASY TIMES TO BE THE CHAMPION

We have shown that we are ready to take countries to the WTO when there is a serious violation of the rules. We just did it again on the Chinese restrictions on exports of rare earths and this particular case is based on our victory on raw materials pronounced in February. We chalked up another success in the Boeing case earlier this month.

We also will not hesitate to use our commercial defence instruments when we see that our companies are being harmed by unfair commercial practices such as dumping or illegal subsidies from our competitors.

Both tools are the key elements of a coordinated implementation strategy and are backed by our strong trade diplomacy, which itself is based on the resources of the Commission and the Member States around the world. These are not the easy times to be a champion of open markets. This is why I am pleased to talk about the trade here with you as commercial representatives.

I have shown you, I believe, that our response to these times of protectionism is to move forward. We have a broad and progressive diary for a European trade policy that moves on all fronts. But to accomplish this agenda we have to have the support of the Member States, the Members of the European Parliament and, above all, the European people.

To do so, we need to win the debate over protectionism. Moreover, companies, and particularly those that play an active role in the global economy, have a crucial role in this debate. As I said, we have a message to broadcast about the need for an open commercial policy. I know you are making efforts to help us, but I have to clarify one thing: companies have to do more to communicate that message in a broad and clear manner.

Too often, the voices of those who wish to promote protection are the most listened to.