In February 2014, the European Commission unveiled the first EU Anti-Corruption Report. The report explained the "anti-corruption situation" in each EU country according to the measures that are in place, which, although working well, could be improved. The idea was to work with EU countries to follow-up on the recommendations from the report. The next version was to be published two years later in 2016. Anti-corruption activists became restless when, towards the end of 2016, the report had not yet been released. Soon after, the media started reporting on the European Commission’s suggestion that the publication would be cancelled altogether.

Not reporting on corruption

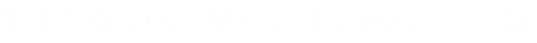

In 2014, the European Commission presented the first EU Anti-corruption Report together with the results from a EU-wide survey, which illustrated the attitudes of Europeans towards corruption. The survey showed that three out of four Europeans considered that corruption is widespread and one out of two that the level of corruption in their country had increased over the past years. Soon the link was made between the perceptions of the Europeans and the impact of the financial and economic crisis that hit many EU countries. The crisis forced EU governments to adopt heavy austerity measures and tough economic reforms. Many Europeans lost their jobs and looked to their political leaders for answers. In 2014, the time and context seemed right for the European Commission to publish such a report with the view of needing to improve transparency, the response to the economic crisis, and address the problem of corruption.

So what made the European Commission decide, two years later, to abandon the idea of publishing a follow-up report on the state-of-play in EU countries relating the fight against corruption? Surely the crisis was still noticeable in many EU countries and the corruption scandals across Europe suggest the problem was far from solved. Not long ago, hundreds of thousands of Romanians took to the streets to protest against corruption and the measures taken by the authorities. In France, a presidential candidate is facing serious corruption allegations ahead of important elections in April 2017, and Spain’s numerous scandals over the years have resulted in the general public perceiving corruption as one of the top three problems in the country.

A survey showed that three out of four Europeans considered that corruption is widespread and one out of two that the level of corruption in their country had increased over the past years

Dropping the baton

Since the first report, the European Commission has renewed and the team under the lead of Jean-Claude Juncker did not only change its organisational structure but also increased its political profile. The Commission services dealing with the topic of corruption were acknowledged by the newly appointed Greek Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos, and also fell under the responsibility of the Commission’s First Vice-President, the Dutch national Frans Timmermans. The increased political profile is seen in the appointment of career politicians with experience in national governments and parliaments. The majority of Commissioners are former ministers (80%) and in the past, a handful have been prime-ministers, including Juncker himself. The political profile of the Commission is not a new phenomenon and despite this, the European Commission as the EU’s executive arm is considered to be performing tasks as a politically independent body.

Nevertheless, this does not mean that there is no risk of political decision-making on initiatives that could affect domestic political affairs. This could be the case, particularly in the Anti-Corruption Report. This, together with more Commissioners involved in anti-corruption work, could have contributed to the decision to cancel the second report. In fact, it was Frans Timmermans who wrote a letter to the European Parliament and first suggested that it would be better if the second report was not published.

A letter is worth a thousand words

The Timmermans anti-corruption letter sets out the European Commission’s anti-corruption work plan. It starts by summing up all the good efforts to strengthen the EU anti-corruption framework, including the first report and a range of workshops in the EU countries on important topics such as asset disclosure, whistle-blower protection, healthcare corruption, local public procurement, private sector corruption and political immunities. Reference is also made to the numerous anti-corruption projects financed by the European Commission as a way to build administrative capacity in EU countries.

Apart from these soft measures, the wider EU policy framework has also evolved. For example, country-specific anti-corruption recommendations have been included in the context of economic policy dialogue with EU countries and EU institutions, the so-called European Semester. These recommendations feed directly into national politics through their adoption by the European Council. According to Timmermans’ letter, the way forward with the European Commission’s anti-corruption work is therefore "to complement the continued focus given to corruption issues in the European semester with operational activities to share experience and best practices among Member States’ authorities and actively working in a wider context alongside international organisations such as the UN, Council of Europe, the OECD, G7 and others who are engaged in valuable anti-corruption work, as well as private stakeholders and civil society organisations". Timmermans further highlights the need for steps to be taken on whistle-blower protection at the EU level, and the already important European legislation on anti-money laundering and public procurement in the fight against corruption.

In addition, efforts are highlighted to increase transparency on issues such as beneficial ownership and corporate tax transparency, as well as the lobbying of EU decision-makers. The EU also has been fighting against fraud and corruption risks in the implementation of EU funds, for example by working on the development of a European Public Prosecutor’s Office. Timmermans reiterates the intention of the European Commission to continue fighting corruption and stresses that it is in the common interest to ensure that all EU countries have effective policies in this area. However, he also questions whether the anti-corruption report in particular would be the best way to proceed in the future.

The EU also has been fighting against fraud and corruption risks in the implementation of EU funds, for example by working on the development of a European Public Prosecutor’s Office

Added value to the EU Anti-corruption report

Timmerman’s letter suggests that with all the efforts to date, the report might not add value in the fight against corruption. When summing up all EU initiatives, one could indeed argue that its contribution is limited. For example, many EU countries are already under scrutiny by other organisations assessing anti-corruption efforts such as the Council of Europe’s GRECO initiative or the OECD’s efforts to harmonize legislation on corruption and bribery. Both international organisations use country peer-reviewing mechanisms to drive authorities to better their policies against corruption.

Such an approach could be less conflictive than the European Commission using the anti-corruption report to push countries to change, especially considering that many related policy areas do not fall under the EU umbrella but rather are a national responsibility. Perhaps a European Commission consisting of former national politicians has taken this into account when questioning the report’s added value. In addition, it is not unlikely that EU countries have been suspicious of the report’s intentions and have pressured the European Commission on this.

The suspicion should also not be detached from misunderstanding on the report’s intentions. These intentions have not been clear from the start, particularly on how the European Commission would follow up with EU countries on identified weaknesses in their anti-corruption efforts. Another criticism on the first report was the fact that it failed to include an assessment of EU institutions. At the time, the anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International decided to conduct its own parallel assessment of ten EU institutions and called for the inclusion of such an exercise in the EU’s Anti-Corruption Report. Any doubts on the legitimacy of the European Commission to criticise EU countries on anti-corruption efforts could this way be crushed when also subjecting itself to an assessment.

However, with the decision to shelf the second report, the European Commission choose to abandon the idea altogether. It is true that steps have been taken to address policy areas relating to corruption. Some of these measures address the EU institutions and others policies in the EU countries. However, it remains a patchwork of measures addressing specific problems, further complicating the EU’s anti-corruption framework. In fact, it is here where the EU Anti-Corruption Report could have made the biggest difference to date. At this point, there are only few EU-wide analyses available providing a more structured overview on the anti-corruption framework in EU countries and in Brussels’ EU institutions. These studies are however often externally funded (by for example the European Commission) and therefore are not necessarily periodically repeated.

In addition, while providing an advocacy component, these studies do not necessarily include follow up processes with stakeholders to improve governance. A clear message coming from such studies is that there are weaknesses in all national anti-corruption frameworks, and that corruption does not stop at borders. In other words, corruption is also an EU problem which thankfully is also acknowledged by the European Commission.

The EU Report has its limitations as a stand-alone document but arguably is indispensible when adopting a wider EU anti-corruption strategy

But taking legislative decisions alone or adopting occasional recommendations for some EU countries does not suffice. Corruption is an obstinate problem and difficult to detect. The European Commission’s report could provide the analytical basis on which it builds its anti-corruption work. It could inform which kind of civil society initiatives to fund or legislative initiatives to launch. It could form the basis of an inclusive and participatory approach to fight corruption, enabling cooperation between civil society organisations, public authorities and companies. The EU Anti-Corruption Report has its limitations as a stand-alone document but arguably is indispensible when adopting a wider EU anti-corruption strategy. The first report has been published and since then, the European Commission has collected data from public authorities and external experts. It would be smart to not let this information go to waste, follow up on a promise, and publish the second EU Anti-Corruption Report. At this stage, deciding not to publish does not only deprives EU the general public from information on an important worry, but also gives the impression that it is not transparent itself and that corruption is winning. After publishing the second Anti-Corruption Report, the European Commission can legitimately question the future of the initiative.