If we make the case to their spokesmen (including treasurers), the transparency of the parties in Spain is quite satisfactory and even excessive: the Treasurer of the PP pleaded recently in the Congress of Members of parliament for the convenience of keeping secret the identity of the donors, a practice openly contrary to all existing international standards, as a way to encourage the increase in scarce private party revenues in Spain.

Even in the Spanish division of Transparency International (TI Spain), in a report from 2015 the Spanish parties obtained a quite good score (8.3 out of 10 on average) in transparency (including financial) and several of them (PSOE, C's, UPyD) reached with honours. This report not only gave rise to a serious slap on the wrist by the Civiocontra Foundation on this IT-Spain initiative in a well-argued post, but it has even generated some internal tensions in this organization and the withdrawal of its website of the two reports on party transparency made in 2014 and 2015 that can no longer be accessed.

This controversy and the continuous wave of evidence accumulated in open judicial research into the main cases of corruption in Spain exhibition that the Spanish parties (we need not add "and the Catalans", right?) are far from being able to guaranteesuch a high level of transparency.Obviously not all of them are the same, but the defects of regulation and supervision of political financing in Spain after the reforms of 2007, 2012 and even 2015 (with a certainly disturbing treatment of foundations linked to parties and a role that our Ombudsman is hardly able to meet) make it quite difficult to lift the shadows of suspicion and opacity that have accompanied these formations since the transition.

Being transparent is not just uploading considerable amounts of information

To be transparent is not just to upload considerable amounts of information and to undergo formal audits.What is involved is to ensure that the accounts that these organisations present are not only credible but one hundred percent real, so that anyone can trust that there is no deception or concealment.Moreover, to achieve this, it is not enough to have optimal regulations however muchNobel-award-of- constitutional-right design it with the best of intentions.The real problem that exists with regard to the regulation of political financing in almost all countries is to ensure that such rules, whatever they may be, are actually respected.However, what we observe is that the level of compliance with all these regulations is relatively low in most countries.

The problem is not so much the existence of regulation or not, nor its level of detail, but rather in the consciousness that the parties have acquired

Effective control over the limits of donations or spending is difficult and costly at all times.In addition, it is the parties themselves that, as legislators, make the rules, so that the will they may or may not have to self-limit is key to making these regulations work.One of the fundamental aspects in which the willingness to self-limitation of the parties can be verified lies in the composition and functioning of the body in charge of ensuring compliance with the regulations.If it is to carry out the supervisory function effectively, it needs to have a clear mandate and sufficient independence, resources and willingness to act.However, we often find that many of these supervisory authorities are too dependent on the parties themselves, lack the necessary resources and do not have a clear mandate to fulfil this function.

In these circumstances, the problem is not so much the existence of regulation or not, nor its level of detail, but rather in the consciousness that the parties have acquired about what is at stake when political financing is notsufficiently transparent and when the rules that determine what can or cannot be done are not worth the paper they are written on.When parties put their funding needs and their willingness to spend in their campaigns above the limits that seem reasonable in each society, the result is the growing distrust and disaffection of the general public towards parties and, ultimately, to democratic politics itself.

Parties have been perceived as the most corrupt institution

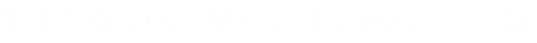

In Spain, this mistrust is absolutely overpowering. Political parties have almost always been the institution perceived as most corrupt by the Spanish in the different editions of the Global Barometer of IT Corruption. In addition, if the problem of the general public's increasing disaffection has pushed most democracies to an increasingly strict regulation of political financing, the Spanish case is extreme compared to the countries around us. The 2013 Eurobarometer data on the low confidence of Europeans in their governments and their political parties. As we can see, the Spanish case is especially dramatic.

Graph: Confidence in government and political parties in the 23 European countries of the OECD

Source: Eurobarometer, 2013 in OECD

Therefore, if confidence in governments and parties is threatened in almost all of Europe, in Spain it reaches particularly worrying magnitudes that make finding solutions quite urgent to improve a situation that will become unsustainable in a short time if we have not already reached the point of no return.

For this, better regulation and supervision is not enough. As the Nordic case teaches us, where lax regulation corresponds to quite a high level of party confidence, technically flawless regulation does not guarantee that parties and donors adjust their real behaviour to the principles of political financing ethics. No matter what the regulations, parties and donors can always find alternative channels to bypass it. So therefore what is important is that the parties are aware of the terrible damage that they do when they violate the credibility of the democratic system by engaging in illicit financing practices.

For this, there are two key aspects to work on. To start with, it has to do with transparency. Only if the general public, associations and media can have access to reliable information about party funding and campaigning can a rational debate take place on which practices attack the basic principles of the democratic regime and can it try to encourage more responsible behaviour on the part of political parties. This is not simply to upload considerable amounts of information, but rather to offer the right tools so that effective control of information is reliable. For example, instead of simply saying how much has been spent on an election campaign, it would be about providing the data that would enable the observer to monitor whether the campaign expenditure actually corresponds to the market-priced cost of services and materials involved in the campaign in question: how many billboards, how many radio wedges, and so on.

However, the second key factor is much more important and explains the exceptional nature of the Nordic case. Beyond the regulation of political financing (the Nordic one has never been an example to imitate, although it has become much stricter recently), trust in parties depends on how the general public judge the way such organisations carry out their main task: the representation of the general public's interests. And on this, the judgment that the Spaniards have is not quite positive.

The general public perceive is that their representatives all too often put the defence of particular interests before the defence of the public interest

Most cases of corruption resemble each other

Most of the cases of corruption that we have seen over the years in democratic Spain have common characteristics. Someone with a particular interest in a particular public decision (awarding a contract, obtaining a licence, introducing a particular regulation...) is able to "buy" the decision that most favours their interest through a direct or indirect payment (which may be of many different types) to the authority and/or public official who has the capacity to take it and/or the party to which such authority belongs. When these cases are revealed, the message received by the general public is that their representatives all too often put the defence of particular interests before the defence of the public interest or the collective interest shared by the electorate of the party to which they belong.

What is different in the Nordic case (and not only in those countries) is that there the incentives that corrupters have been able to corrupt to those who make the public decisions that affect their interests have been much smaller. Not because they did not have the same economic interest as in countries where the practice of corruption is more widespread, but because they were much more difficult to corrupt these decision makers. While in countries such as ours, the political authorities have a margin of discretion which is much broader and have a much higher capacity to counteract the professional resistance of public managers and technicians (civil servants) in making such decisions, than in cases of countries conspicuous for their high quality levels of government. The area reserved for the influence of management professionals, as well as the strong professional ethics that is expected of these agents, makes it much more difficult that any particular entrepreneur can obtain more favourable treatment in exchange for "investing" in the financing of a particular party.

No matter what the rules, parties and donors can always find alternative channels to bypass it

Improving the dramatic levels of distrust in political parties and politicians in Spain should therefore not only improve the regulation of political financing and transparency of political parties, but also decisively raise the quality of our government institutions, their professionalization and their depoliticization. Better for us not waste time focusing on what political magicians want to show us (as, for example, the amount of information that is now on their portals compared to its scarcity in the past) so as not to lose sight of the pea under the thimble: the exercise of power that benefits particular interests at the expense of the interest shared by all or at least by the majority.